How to Practice Acceptance Without Being Complacent

By Dave Potter, guest contributor

The concepts of “acceptance” and “non-striving" in mindfulness practice are difficult to understand because they seem to imply passivity and inaction. I don’t think I’ve ever taught a mindfulness class in which a student didn’t question mindful “acceptance” with concerns that it would lead to passivity:

“How does “acceptance” and “non-striving” apply when being attacked, verbally or physically?”

But “acceptance”, in the context of mindfulness, does not imply passivity. It does not mean that we give in to abuse, that we ignore our values, or that we give up when we encounter obstacles. Mindful “acceptance” means that we fully acknowledge the current moment (external situation as well as feelings, thoughts, and perceptions) so that we can respond appropriately in the next moment. For example, a mindful response could be forceful and energetic, or gentle and soothing, or simply pausing for a moment (see STOP) to allow an appropriate response to emerge.

Years ago, I was called to a board meeting of a non-profit organization on which I served, after the board discovered that the president had done something they had expressly forbidden. The president had not been invited to the meeting, and although everyone agreed he had done a great job up until that point, they were so angry that they wanted to fire him immediately, without notice, and without even giving him a chance to explain. I felt strongly that this was wrong, but it was so clear that there was no talking the others out of it, that I sat quietly as they continued to loudly voice their upset about what he had done.

But then, I surprised even myself when I blurted out, “We can’t just fire him without even giving him a chance to respond!! It’s unfair and doesn’t take into account the great job he’s done until now. We need to at least give him the option to resign so he can retain some dignity.” The other members of the board sat in stunned silence for a moment, but then an animated discussion followed as they reconsidered their approach. Ultimately, the board decided unanimously to give him an opportunity to respond and the option to resign.

“Acceptance” in the conventional sense would have meant that I continued to be silent and go along with the others, but another kind of “acceptance” was going on here. What I accepted was the reality that the board members were angry, that they felt dismissed, and that I felt strongly that what they were proposing was wrong and unjust. My protest emerged spontaneously from my acceptance of these multiple and seemingly conflicting realities. Yet, I didn’t feel any internal conflict because my response came from a place deep within me. It was heart-felt and anything but passive, and my self-worth did not depend on their agreeing with my point of view.

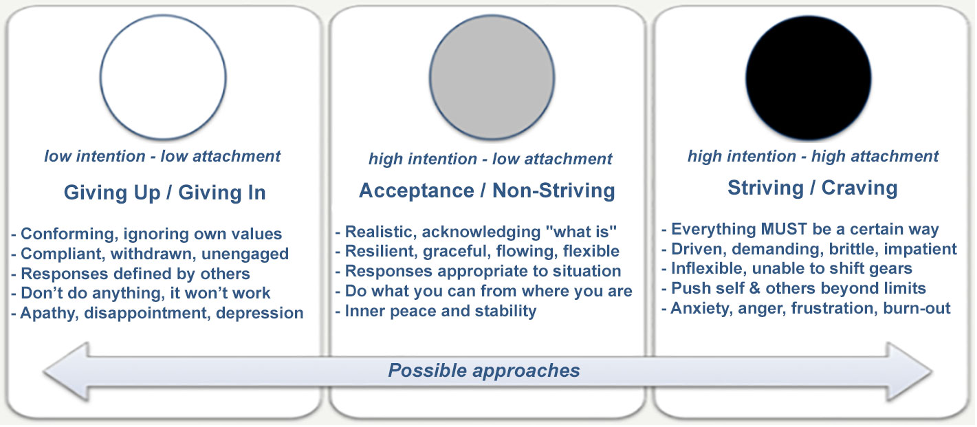

Another way to understand how mindful acceptance differs from the conventional meaning of “acceptance” is to make a distinction between intention and attachment. Intention is the degree to which we are committed to a certain value or outcome, how much time and energy we are willing to dedicate to make something happen. Attachment is more subtle, a measure of how much we are emotionally entangled with our own expectations and projections. In the previous example, I felt strongly that we, as a board, owed the president a chance to respond (high intention), but I was ready to accept a different decision if the rest of the board could not be convinced (low attachment).

The illustration below shows three of the four possible combinations of intention and attachment:

[ Thanks to Liv Downing for the inspiration for this illustration. See Acceptance is not Giving Up, it is Waking Up. ]

NOTE: The fourth combination, low intention/high attachment, is wishful thinking: no investment of energy but a strong desire for a specific outcome, like never bothering to apply to medical school but really wanting to become a doctor.

The combination of high intention and low attachment is the sweet spot, making it possible to have all the energy and drive of “high intention”, but with the ease and calm of “low attachment”. High intention allows us to stay true to our values and goals, while low attachment allows us to act from a grounded and stable place. Even when things don’t go as expected, our emotional energy can be used to find a new strategy, not wasted catastrophizing or obsessing about what “should have been”.

My wife’s Ph.D. advisor, Bill, understood the importance of “acceptance” even while pursuing a challenging goal. On his office wall was a replica of a sign he saw on a New Delhi golf course, where monkeys were literally one of the course hazards, that said:

Whenever a doctoral student complained about something being unfair (life, the university, him), Bill would point to the sign. Students usually laughed and got on with their lives and studies.

Another of Bill’s favorites was:

The trick is, to take yourself seriously without taking yourself seriously.

The problem is, most people get it backwards.

Like a zen koan, this doesn’t make sense at first, but its deeper meaning is high intention and low attachment, the possibility of “acceptance” and “non-striving” even while working hard toward an important goal.

“Wu-wei” (無爲) is a Chinese term which literally means “non-doing”, but it has a secondary meaning which is “effortless action”. In Taoism, wu-wei is a state in which a person may be intensely active and engaged externally, but internally, they are calm. Like the graceful athlete who is “in the zone” or a skilled sculptor wielding a chisel, action flows naturally from a place of inner stillness and in perfect alignment with body, mind, heart, and spirit.

Mindfulness practice offers the possibility of living our lives this way, able to respond to any situation appropriately, from this place of inner stillness, whether it be with decisiveness and high energy, or with gentleness and a soft touch.

Of course, staying in the sweet spot of non-striving and inner stillness, while dealing with difficult issues, is easier said than done, and we don’t always get it right. But mindfulness practices help build this skill. Sometimes I tell students that being mindful does not mean you will be peaceful all the time, but through mindfulness, you can discover that it is possible to be at peace with not feeling peaceful.

------

Dave is a retired psychotherapist and is fully certified as an MBSR instructor by the UMass Medical School where MBSR was founded by Jon Kabat-Zinn. The free online MBSR course he created in 2012, Palouse Mindfulness, is based on the 8-week in-person MBSR class he taught to 400 people over a span of 10 years. For more on this topic from a past Palouse Mindfulness Graduate meeting, see Acceptance / Non-Striving.

What are your thoughts? Please share comments and questions below.

1 comment

Acceptance is a powerful emotional and mental tool. It helps us face reality as it is—without resistance, denial, or distortion. But many people confuse acceptance with giving up or becoming complacent.

Leave a comment